A Tribute to the Brits!

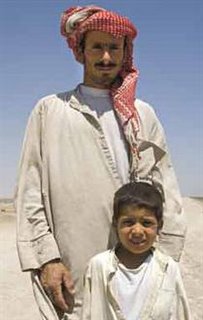

Iraq's former President, Saddam Hussein, did his best to drain the wetlands of south-eastern Iraq, but now they are being flooded again, and with the water's return has come a revived way of life for the Marsh Arabs. British forces are helping them and making some important friends.

Flight Lieutenant Guy Wood was a policeman in Hackney before joining the RAF Regiment, and the job he has now, as second in command of 3 Squadron, is not so very different – if you ignore the 50 degree heat, the occasional camel, and the danger from Improvised Explosive Devices.

Like any good copper, he makes it his business to know everyone else's business on his patch: what's new, what people's concerns are, and if there are any bad eggs in the neighbourhood.

"Our interaction out and about in the villages and towns is to try and provide security for the Iraqis as much as for ourselves, so they can start rebuilding their lives," he says. "There are a number of people who have probably never laid eyes on westerners, and our role here is to build those bridges."

On the way to the village, "Woody" is quite happy for me to ride top cover with him, my upper half poking out of the roof of the snatch Land Rover. It's only when we come to the Shatt Al-Basra Canal, and stop to allow the soldiers to make a thorough examination of the bridge and the road leading up to it, that it strikes me we are not in entirely friendly territory, and I am exposing an unnecessarily large proportion of my civilian body to the possibility of hostile fire (I am taller than my companion by more than a head).

Both the village we are bound for now and one which we visited earlier in the day are incorporated in the Al-Shaggambah tribe, one of the biggest tribes in southern Iraq. Their goodwill is vital if British forces are to continue doing their job effectively.

They provide a secure home base for us to use the roadways and bridges to get across into the less accommodating parts of our area," Flt Lt Guy Wood says. "They know they are tactically significant, and they're certainly not blind to how advantageous it is to us for them to be there."

As we are crossing the bridge, we are passed by a car carrying the 'servant' of the Sheikh – the village leader. News of our approach will go ahead of us, Woody says, and they will make preparations.

On the far side of the bridge the grey of the desert gives way to green. The marshes are relatively dry at this time of year, but there is still a lot of water about. There are fishing boats, wading birds, and reeds as far as the eye can see.

The patrol is still cautious, however. Coming across a pile of stones that hadn't been there on their previous drive along this stretch of road, the vehicles halt and someone walks ahead to investigate what turns out to be a temporary shelter. It's a reminder that herons are not the only things to come flying out of this peaceful landscape.

The road we travel on is no more than the flat top of a levee dividing one stretch of marsh from another. In the winter it will be nothing but a hump of mud, impassable to wheeled vehicles.

Flt Lt Wood says the RAF Regiment's 'policing' role is about building a rapport with individual Iraqis and finding common ground – however difficult that might be when some of the local population perceive the Coalition to be an occupying force.

"All the troops are doing is employing their interpersonal skills," he says. "With such a generous and welcoming people as the Iraqis even the smallest of gestures goes a long way. It's rewarding work, and going out and interacting with the people is great for anybody. They're very hospitable people, and it can be quite humbling, as they are as close to poverty as you're going to get."

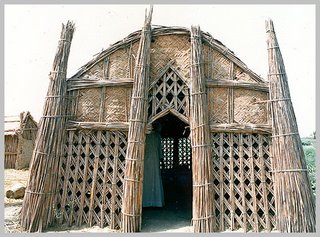

When we reach the village, the first building we see is the mudhif, a sort of town hall made entirely of reeds and used for resolving tribal disputes. It is also a place where guests are received. We are invited in, and it is like being inside a giant wicker animal, a profoundly peaceful space. Light filters in beneath the arching ribs. The building would probably work its magic on disgruntled tribesmen.

Woody has some business with the Sheikh, and while we are waiting we look around at the buffalo and at the sunset and the children crowded round the vehicles. It's a vision of Biblical – or Mesopotamian – calm.

Life in these rural backwaters can be a culture shock for some of the younger soldiers. Corporal Trevor Ford, making sure adventurous village children don't get into the back of his Land Rover, is impressed with the struggle the locals have just to survive.

They've had a remarkably tough time," he says, "And they just get on with it. It's awesome. I've seen these kids out gathering reeds at four or five o'clock in the morning, after prayers."

A few minutes later Woody reappears, looking distinctly unhappy. "We've been invited to a feast," he tells us, grimly, knowing that the rest of the patrol will have to be postponed while we do justice to the food.

In the middle of the village carpets have been put down and food laid out. Sheikh Muzir, a powerful man with responsibility for some 30,000 people, looks on as we try to do justice to his food. Unfortunately we all ate a full meal before leaving the base only an hour or so before, and seem likely to fail in the attempt to clear our plates. As one soldier admits defeat and washes his hands (no knives or forks here), another is called away from guard duty to take his place. The roasted fish is delicious, as is the dish of rice and sultanas that accompanies it.

It's a great experience for everyone. But sitting down to a meal with strangers is also the beginning of all diplomacy. Once you have broken bread with someone, so the ancient laws of hospitality say, you have created a special bond.

We are under no illusions that part of the reason for this invitation is that the Sheikh wants a Coalition-funded development project here. But that's fair enough. We are here to win friends, and, wherever you are in the world, there is no such thing as a free dinner.

This article, by Roy Bacon, first appeared in the September 2006 issue of Focus, the newspaper for people in defence.

No comments:

Post a Comment